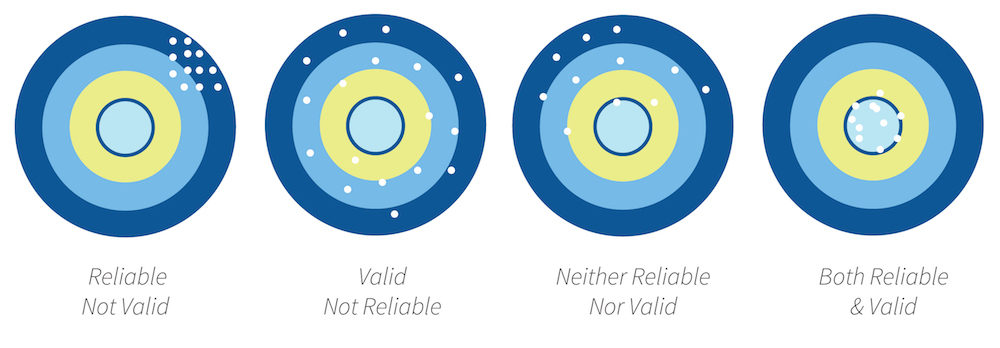

Nevertheless, the miscalibrated weight scale will still give you the same weight every time (which is ten pounds less than your true weight), and hence the scale is reliable. In the previous example of the weight scale, if the weight scale is calibrated incorrectly (say, to shave off ten pounds from your true weight, just to make you feel better!), it will not measure your true weight and is therefore not a valid measure. Note that reliability implies consistency but not accuracy. A more reliable measurement may be to use a weight scale, where you are likely to get the same value every time you step on the scale, unless your weight has actually changed between measurements. Quite likely, people will guess differently, the different measures will be inconsistent, and therefore, the “guessing” technique of measurement is unreliable. In other words, if we use this scale to measure the same construct multiple times, do we get pretty much the same result every time, assuming the underlying phenomenon is not changing? An example of an unreliable measurement is people guessing your weight. Reliability is the degree to which the measure of a construct is consistent or dependable. Comparison of reliability and validity Reliability Hence, reliability and validity are both needed to assure adequate measurement of the constructs of interest.įigure 7.1. Finally, a measure that is reliable but not valid will consist of shots clustered within a narrow range but off from the target. A measure that is valid but not reliable will consist of shots centered on the target but not clustered within a narrow range, but rather scattered around the target. Using the analogy of a shooting target, as shown in Figure 7.1, a multiple-item measure of a construct that is both reliable and valid consists of shots that clustered within a narrow range near the center of the target. Likewise, a measure can be valid but not reliable if it is measuring the right construct, but not doing so in a consistent manner. Reliability and validity, jointly called the “psychometric properties” of measurement scales, are the yardsticks against which the adequacy and accuracy of our measurement procedures are evaluated in scientific research.Ī measure can be reliable but not valid, if it is measuring something very consistently but is consistently measuring the wrong construct. We also must test these scales to ensure that: (1) these scales indeed measure the unobservable construct that we wanted to measure (i.e., the scales are “valid”), and (2) they measure the intended construct consistently and precisely (i.e., the scales are “reliable”). Hence, it is not adequate just to measure social science constructs using any scale that we prefer. For instance, how do we know whether we are measuring “compassion” and not the “empathy”, since both constructs are somewhat similar in meaning? Or is compassion the same thing as empathy? What makes it more complex is that sometimes these constructs are imaginary concepts (i.e., they don’t exist in reality), and multi-dimensional (in which case, we have the added problem of identifying their constituent dimensions).

The previous chapter examined some of the difficulties with measuring constructs in social science research.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)